Ensuring Patients with MS Receive Prompt Diagnosis and Treatment

In MS, time is brain

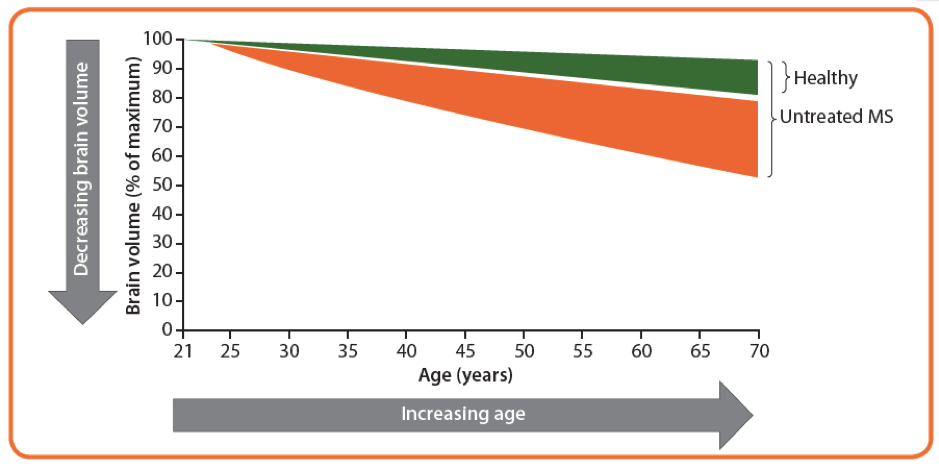

In all patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), the degeneration of neurons and axons leads to brain atrophy.1,2 The longer the patient is without diagnosis and effective treatment, the more of the brain and spinal cord that will be irreversibly lost (Figure 1).2

Figure 1:2 A theoretical example depicting brain atrophy rate in an untreated patient with MS and a healthy control. Accelerated brain atrophy starts at disease onset, in this case at the age of 25 years, and continues throughout the disease course if left untreated.

In the early stages of the disease (for example, in many patients with clinically isolated syndrome [CIS] or early MS), the repair mechanisms of the CNS are complemented by neurological reserve, whereby functional neurons can compensate for damaged ones allowing the brain to remodel itself .2 However, if brain atrophy continues unchecked, the neurological reserve will eventually be eroded.2 There is, therefore, an onus on neurologists to ensure patients with suspected MS receive prompt investigation and diagnosis, and that those patients with CIS or MS receive treatment in a timely fashion.2 This article considers, what constitutes prompt diagnosis and timely treatment, as well as what clinicians can do to ensure they are carried out.

Initial presentation and diagnosis

Owing to remarkable repair mechanisms in the CNS, along with neurological reserve, symptoms related to early brain atrophy are difficult to recognise;2 patients with higher active cognitive reserve have a lesser symptom burden.3 This may provide a longer “runway” until disability accrual.3 If patients with CIS, during this “runway” period, are investigated using cognitive batteries, e.g. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, they often have cognitive impairment; and investigation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), reveals structural brain changes, for example atrophy of the fronto-temporal region, thalamus and deep grey matter, compared with healthy matched controls.4,5

Delays may occur at distinct stages of the diagnostic process.2 Firstly, there may be a delay between the initial symptoms and the first healthcare professional consultation, caused by a lack of patient awareness and knowledge, as well as fear. This delay can be up to and over a year in duration.2 Secondly, there may be a delay between initial consultation and referral to a specialist neurologist with the experience to provide an accurate diagnosis. This delay may point to unmet educational needs among primary care physicians.2 Finally, waiting lists and unavailability of diagnostic tools may cause delay.2 There is evidence showing that the longer the time before referral to an MS neurologist, the higher the disability level at first visit, highlighting the important of minimising the time that these two potential delays have on the diagnostic process.6

Being able to discount an MS diagnosis in suspected MS patients is also important.7 The misdiagnosis of a chronic, incurable, progressive disease is likely to have an avoidable psychological impact on the patient.2 This misdiagnosis may also cause unnecessary exposure to disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), which are associated with long-term side effects including serious opportunistic infections, the development of other autoimmune conditions and cancers.7 One red flag that neurologists should be aware of regarding misdiagnosis is if the initial neurological symptom occurs at an older age, as vascular disease is most likely to be the underlying cause here.8

Benefits of early intervention

There is compelling evidence for the benefit of early disease intervention; for example, an analysis of a cohort of 11,934 patients with relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS) from the Big Multiple Sclerosis Data Network evaluated the relationship between DMT start and the first occurrence of Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) progression.10 The optimal time to start DMT to prevent long-term disability accumulation was within 6 months from disease onset. Overall, the sooner a DMT was initiated, the higher the probability that the patient would reach 12 months with no confirmed EDSS progression (Figure 2).10

Figure 2: Adapted from Iaffaldano P, et al. 2018.10 A Kaplan–Meier curve showing the probability of reaching a 12-month confirmed EDSS progression. Q1 to Q5 represent the stratified groups by quintiles of time from disease onset to the first DMT start, years, median (interquartile range)

Compared with delayed therapy, early initiation of injectable DMTs in patients with CIS lowers relapse rate, brain atrophy and disability progression (clinically definite MS [CDMS] conversion risk).1,7,11,12 These benefits are possibly due to an early effect on immune regulation, or a better-preserved compensation capacity reducing the consequences of inflammatory attacks.1

Having considered the numerous studies showing that DMTs prevent future disability in patients with CIS, international experts and MS organisations have recommended that injectables are used in patients with CIS and those with abnormal MRI lesions suggestive of MS.7,13,14 Despite this, the decision-making process to choose the right medication for an individual patient is a complex task; there are many medications now available for the treatment of MS, with different routes of administration (e.g. oral or subcutaneous), different mechanisms of action, effectiveness and safety profiles.14 Neurologists are now required to evaluate carefully the results of clinical trials, use up-to-date information from post-marketing data and be capable of critically translating data from studies (that include carefully selected patients) to patients in everyday clinical practice.14

How can you ensure prompt diagnosis and intervention?

Many leading MS neurologists endorse prompt diagnosis, timely interventions and regular proactive monitoring of treatment effectiveness and disease activity. The Delphi Consensus Panel, consisting of 21 MS neurologists from 19 countries, provided a consensus on achievable clinical standards for the timing of key events in the MS care pathway. This pathway focuses on referral and diagnosis, priorities following diagnosis, treatment decisions, routine monitoring and support and new symptoms (Figure 3).15 According to these achievable standards, when a patient presents with symptoms, they should expect to be referred to a neurologist within 10 days, undergo MRI within 2 weeks of referral and have diagnostic workup completed within 4 weeks of referral. After diagnosis, the patient should be assessed for eligibility for early treatment with a DMT within 3 weeks.15

Figure 3. Adapted from Hobart J, et al. 2019.15 Achievable consensus standards for the timing of key events in a brain health-focused pathway.

Refining clinical processes to maximise MS outcomes, as suggested by the Delphi Consensus Panel,15 is complemented by effective use of diagnostic biomarkers.8 It is recommended to analyse cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from a lumbar puncture, which can help to identify MS mimics and either support or refute a diagnosis of MS.8 The presence of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands (OCBs), along with typical CIS and clinical or MRI demonstration of dissemination in space, allows a diagnosis of MS to be made according to the most recent 2017 McDonald criteria.16

Biomarkers have potential to help in treatment selection now and in the future

The use of biomarkers extends beyond MS diagnosis; biomarkers are now applicable to a variety of stages throughout the management and treatment of patients. MRI lesion load (number of T2 lesions), OCBs and age at CIS have been validated as predictors of CIS to CDMS conversion.17 Neurofilament light chain protein has also been shown to have potential as a prognostic biomarker, and could be used to monitor disease progression, disease activity and treatment efficacy.18 This biomarker is elevated not only in CSF, but also in the blood of patients with MS, making it a potentially more practical option than CSF-only biomarkers, which require lumbar puncture.18 Retinal imaging using optical coherence tomography (OCT) has provided other promising biomarkers. OCT-detected decrements in retinal nerve fibre layer thickness and ganglion cell layer–inner plexiform layer thickness are markers of axonal damage and neuronal injury, respectively.19 These have been shown to correlate with worse visual outcomes, increased clinical disability and MRI-measured burden of disease in patients with MS.19

Achieving highly specific and sensitive MS biomarkers is a continuous goal for MS researchers, but currently such a test remains elusive.7 There is some evidence suggesting that novel imaging techniques, e.g. fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI, have greater specificity for a diagnosis of MS than the current MRI approaches.7 Furthermore, other CSF biomarkers have been proposed for use in differential diagnoses, e.g. chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 13 (or CXCL13).20 However, with these multiple different variables that need to be considered, algorithms including MRI, OCT and the best CSF and/or serum biomarkers could guide neurologists in future decision making.20

Conclusions

In MS, time is brain, and together we can help to achieve early diagnosis and therefore identify the brain when it has been subject to least damage.2,15 This allows early intervention with DMTs, ideally within 6 months of diagnosis, which has been shown to have benefits for long-term disease outcome.1,10,11 To make this achievable, biomarkers will be indispensable tools for diagnosis, treatment assessment and assessment of prognosis of patients with MS now and in the future.7,17–20

References

-

Hartung HP, et al. J Neurol. 2019 [Epub ahead of print]

-

Giovannoni G, et al. Brain Health. 2018. Available at: http://www.msbrainhealth.org/report

-

Schwartz CE, et al. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:1971–1981

-

Hynčicová E, et al. J Neurol. 2017;264(3):482–493

-

Diker S, et al. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;10:14–21

-

Kingwell E, et al. J Neurol Sci. 2010;292:57–62

-

Solomon AJ, et al. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:567–572

-

Dobson R, et al. Eur J Neurol.2019;26:27–40

-

De Stefano N, et al. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(2):147–156

-

Iaffaldano P, et al. Presented at ECTRIMS 2018 [Abstract 204]

-

Comi G, et al. Mult Scler. 2013;19(8):1074–1083

-

Armoiry X, et al. J Neurol.2018;265:999–1009

-

Montalban X, et al. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96–120

-

Ghezzi A. Neurol Ther. 2018;7:189–194

-

Hobart J, et al. Mult Scler.2018;1–10

-

Thompson AJ, et al. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:162–173

-

Kuhle J, et al. Mult Scler. 2015;21(8):1013–1024

-

Cai L, et al. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2241–2254

-

Costello F, et al. Eye Brain. 2018;10:47–63

-

Thouvenot E. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2018;174:364–371

לאילו מצבים רפואיים קנביס רפואי יכול להועיל?

קראו עכשיו סיכום של מחקרים שבדקו את השפעת הקנאביס הרפואי על מצבים רפואיים שונים

לקריאה>>כתבות נוספות שאולי יעניינו אותך

רוצים להמשיך לקרוא?

הירשמו עכשיו בקלות ובמהירות לאתר התוכן של טבע ישראל לקהל הרפואי ותקבלו גישה לכל התכנים

להרשמהאת.ה עומד.ת לעזוב את העמוד

האם את.ה בטוח.ה?