Family Planning in Patients with MS

The increasing importance of family planning in MS

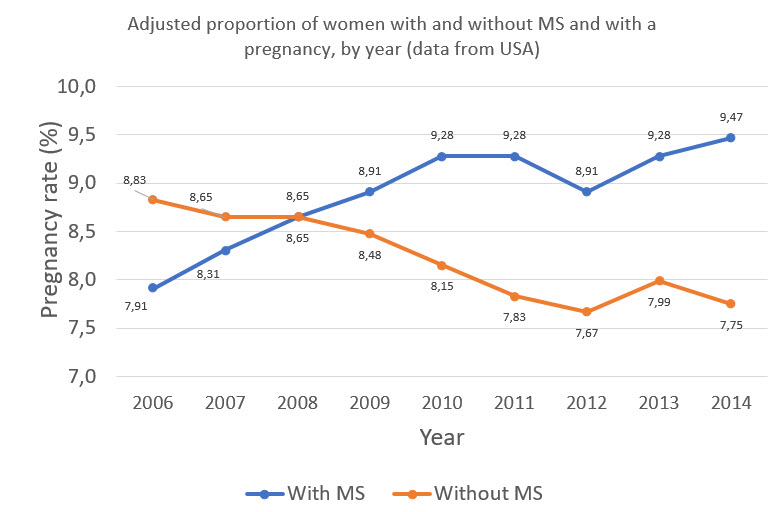

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common acquired neurological disorder of young adults globally, with the typical patient with MS being a young woman at reproductive age. The disease shows a female predominance that is now approximately 3 to 1, and this gender bias is expected to become more pronounced with MS on the rise in young women. Between 2006 and 2014 in North America, pregnancy rates in women with MS increased significantly while pregnancy rates in general declined (Figure 1). This suggests that clinicians are becoming more comfortable managing the complex reciprocal effects of MS and pregnancy, and that significant efforts among MS specialists to educate the public and general neurologists are allowing more women with MS to start a family. Despite this increase, more real-world evidence to inform decision making in women with MS of childbearing age is still required.1–3

Figure 1: Adapted from Houtchens MK, et al. 2018.3 The changing proportions of pregnancy rates in patients with and without MS in a US cohort.

In this article, we will look at the impact that pregnancy has on MS prognosis and the counselling and treatment considerations for neurologists before, during and after pregnancy. Relapse treatment options during pregnancy and how male patients with MS are impacted are also considered.

Pregnancy and MS prognosis

There is a considerable amount of data regarding the effect of pregnancy on the course of short-term MS. The Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis (PRIMS) study initially suggested a protective effect of pregnancy on short-term prognosis. However, it is now considered that the effect of pregnancy is more complex than initially thought: there is a reduction in the number of relapses during pregnancy, specifically during the third trimester, but there may be reactivation of MS inflammatory activity during the postnatal period, along with a short-term relapse peak. However, recent data from the American Academy of Neurology has challenged the idea that women with MS can expect their disease to worsen after pregnancy. This study, which analysed 466 pregnancies among 375 women in the USA, showed that the annualised relapse rate (ARR) for women in the first 3 months postpartum (0.27) was even slightly lower than before pregnancy (0.39).4–8

These proposed changes in relapses during gestation and after delivery are thought to be caused by hormonal and cytokine changes: pregnancy is associated with downregulation of cell-mediated immunity, resulting in a shift towards a T helper 2 (Th2) cytokine profile. This shift leads to reduced levels of Th1 cytokines (interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor α) and increased levels of Th2 cytokines (interleukins 4 and 10), which are essential for tolerance of the foetus during pregnancy. The beneficial immunomodulatory effects of high levels of oestrogen during pregnancy may explain the overall reduction in MS activity during gestation.4

Pregnancy is associated with better outcomes compared with nulliparous regarding long-term disability progression in MS. A 2015 retrospective study of 445 women found that the risk of reaching Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) ≥4.0 or ≥6.0 was lower among patients who had been pregnant after MS onset than those who had never had children. Furthermore, data from the large MSBase database showed that over a 10-year period, EDSS scores in participants with at least one pregnancy were lower than those who had never been pregnant.4,5,9

Pre-pregnancy considerations and management approaches

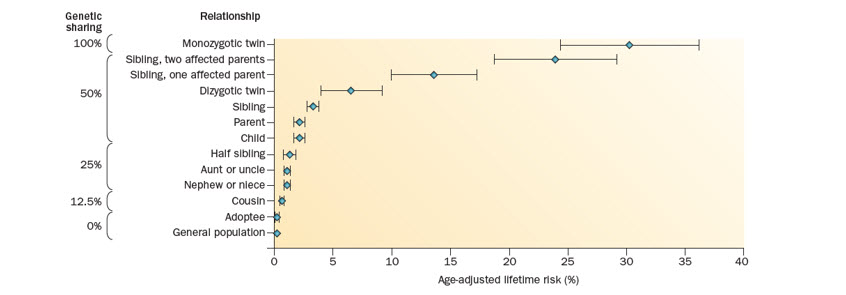

Uncertainty around the heritability of MS in women considering pregnancy can be managed by communicating the low risk of passing on the disease; the age-adjusted lifetime risk of MS in children with one parent with MS is 2%, which is 20-fold higher than expected in the generalpopulation from Western countries, but still considered low (Figure 2).10

Figure 2: From Vukusic S, et al. 2015.10 Risk of MS among family members of affected individuals

Although MS has no direct negative effect on fertility, MS can complicate conception indirectly. Sexual dysfunction (SD) is an important symptom of MS, affecting 40–80% of women with MS. Primary SD symptoms include altered genital sensation, decreased libido, problems with arousal and orgasm, and decreased vaginal lubrication. When infertility arises coincidentally with MS, patients may require assisted reproductive treatment (ART). Multiple studies have showed an increase in ARR after ART, and this clinical worsening was associated with an increase in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) activity. Although, in all of these studies the patients discontinued disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) during ART. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, frequently used as part of in vitro fertilisation (IVF), decrease oestrogen levels, which could remove the protective effect of this hormone. In theory, according to an evidence-based recommendations paper by Fragoso et al, GnRH antagonists should be the better option because they do not lead to oestrogen decrease. However, a significant increase in ARR was specifically observed after IVF when using a GnRH agonist.11–14,4

Vukusic et al suggest that as soon as a woman with MS is considering pregnancy, a treatment plan should be established. The practical recommendation from Fragoso et al regarding pregnancy for women with MS is that disease control should be achieved before conception. However, considering that in the US general population in 2006, nearly half (49%) of pregnancies were unintended, disease control early in the treatment course is important for women of childbearing age with MS. There is a debate on whether to continue or stop treating the patient with DMTs once the patient is trying for a baby and if you choose to stop the DMT, how long the washout period should be for your patient. 10,4,15,16

In the USA, a large proportion of women with MS use DMTs when approaching conception: among 984,058 pregnancies in patients with MS, 35% filled a prescription for a DMT 90 days before pregnancy. In a survey of neurologists (n=216) working in Europe, respondents were divided on this question (50% said stop immediately and 49% said stop after conception).In those respondents who chose to stop treatment immediately, the suggested washout periods varied significantly between DMTs, and in some there was no majority decision regarding the duration of washout period before conception. Overall in this survey, injectables had the shortest recommended washout period.16,17

The EAN/ECTRIMS consensus recommendation is to advise all women of childbearing potential that DMTs are not licensed during pregnancy, except glatiramer acetate (GA) 20 mg/mL. A weaker recommendation is to consider INF-β or GA until pregnancy is confirmed in patients with a high risk of disease reactivation. In some very specific highly active cases, continuing treatment during pregnancy could also be considered. For women with persistent high disease activity, EAN/ECTRIMS advise delaying pregnancy; for those who, despite this advice, still decide to become pregnant or have an unplanned pregnancy, EAN/ECTRIMS give some suggestions for suitable high-efficacy treatments (see guideline for details). Vukusic and Marigniersuggest that for patients receiving an agent that requires a washout period before trying to become pregnant (and for which active contraception during this period is warranted) the clinician and patient could discuss the possibility of switching to a safer bridging drug until pregnancy begins.18,19,10

During pregnancy considerations and management approaches

Pregnancy in women with MS is not considered a ‘high-risk’ pregnancy and according to Coyle and colleagues, patients should be counselled that MS in itself has no significant impact on foetal development and ability to carry to term. Monitoring considerations also need to be made in pregnant patients with MS. For example, the UK recommendations are that gadolinium contrast media should be avoided in MRI where possible.4,1,19

The health of the foetus needs to be heavily considered in treatment decisions. It is important to note that foetal exposure to drugs used in MS treatment does not constitute a reason for abortion. In a study with 101 DMT-exposed and 78 non-DMT-exposed pregnant patients with MS, no difference except non-significant changes in miscarriage rate and lower birth rates were observed. In a further study, pregnancies with and without early DMT exposure had a similar risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (e.g. spontaneous abortion) to one another and to pregnancies in women without MS.4,1,17

There is considerable data on exposure of the foetus to injectables. Exposure to injectable DMTs was not associated with an increased risk of general teratogenic effects, congenital anomalies, low birth weight and preterm birth.20–22

Epidural and general anaesthesia in women with MS is possible,as they are not associated with an increased relapse risk and do not influence disease activity postpartum. However, a lack of data means that a possible minor increase in the postpartum relapse rate after use cannot be ruled out.7,10

Postpartum considerations and management approaches

Breastfeeding is a major part of the treatment decision-making process. There are benefits of breastfeeding for the baby and the World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life to achieve optimal growth, development and health of the baby. There is also a potential benefit for the mother with MS or clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), and the recommendation by Fragoso et al is to encourage breastfeeding for its beneficial effect as a whole. In a study of 397 patients with newly diagnosed MS or CIS and 433 matched controls, breastfeeding for ≥15 months was associated with 53% reduced odds of developing MS or CIS. In a separate study with 210 pregnancies in women with RRMS, exclusive breastfeeding for ≥2 months reduced the risk of postpartum relapse. Breastfeeding appears to act like a treatment: it has a stop point and disease activity returns when breastfeeding stops. However, Hellwig et al highlight that these data should be interpreted with caution because patients with less active disease are more likely to breastfeed.23–25,4

In general, DMT use increases after delivery, but Vukusic et al recommend that breastfeeding and treatment options after delivery should be discussed to outline the options for prevention of postpartum relapses, and the possible resumption of DMTs.There are limited data informing use of DMTs during breastfeeding. In cases of high disease activity and for those women who do not want to breastfeed, Thörne and colleagues recommend early (7–10 days postpartum) reintroduction of DMTs be considered. However, convincing data on reduction of postpartum relapses are lacking.17,10,4,1,7

Non-DMT and relapse treatment options during pregnancy

Up to a quarter of pregnant women with MS or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder suffer from a clinically relevant relapse during pregnancy. Relapses during pregnancy, particularly during the first trimester, should be treated with corticosteroids only when they significantly affect the mother’s activities of daily living according to Fragoso et al. This is because of risk of orofacial cleft and miscarriage. However, the UK recommendations are that intravenous methylprednisolone should be offered at the recommended dose for women with MS suffering a disabling relapse, until the underlying infection has been excluded, regardless of the trimester. In a recent study, tryptophan immunoadsorption was found to be well tolerated and effective after insufficient response to steroid pulse therapy and as a first-line relapse treatment during pregnancy and breastfeeding.2,4,19

There are conflicting data regarding the use of antidepressants during pregnancy and they may have a small effect on foetal growth. Fatigue and cognitive dysfunction treatments have been proposed with only anecdotal evidence and generally lack evidence for recommendation. There are no drugs for use in improving gait velocity and spasticity that may be used during pregnancy.4

Reproductive considerations for male patients with MS

Sexual dysfunction affects 50% to 90% of men with MS. These symptoms include erectile dysfunction, ejaculatory dysfunction, orgasmic dysfunction and reduced libido. Furthermore, there is an association between male infertility and MS: relative to control subjects, men with MS have been reported to have lower baseline levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone and testosterone.4,26

Concerning fertility issues, the effects of or immunomodulating drugs on semen quality are largely unknown, whereas many immunosuppressive therapies have a negative effect on semen quality that may be definitive. Among first-line therapies recommended for patients with low disease activity, the use of injectable DMTs in men at time of conception has not been associated with worse neonatal outcomes. Clinicians should remain vigilant for possible adverse foetal outcomes caused by paternal preconceptional and conceptional medication.4,26–29

Conclusions

The management of MS in the context of family planning is a balancing act and should be considered on an individual basis, where communication and collaboration between doctor and patient is important. MS used to be a reason not to have children, but it is now a potentially controllable disease. However, disagreements regarding the best treatment approaches for MS indicate the need for further clarity and evidence-based recommendations and/or guidelines.10,6,16

References

-

Coyle P. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016;9(3):198–210

-

Hoffmann F, et al. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018;11:1–12

-

Houtchens MK, et al. Neurology. 2018;91(17):e1559–69

-

Fragoso YD, et al. Neurol Ther. 2018;7(2):207–32

-

Zuluaga MI, et al. Neurology. 2019;92(13):e1507–16

-

Confavreux C, et al. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):285–91

-

Thöne J, et al. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017;16(5):523–34

-

American Academy of Neurology. Good news for women with MS: Disease may not worsen after pregnancy after all. (7 March 2019). Available at: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/03/190307161929.htm (accessed May 2019)

-

Masera, et al. MSJ. 2015;21(10):1291–97

-

Vukusic S, et al. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280–9

-

Demirkiran M, et al. Mult Scler. 2006;12(2):209–14

-

Miller AE. Mult Scler. 2016;22(6):715–16

-

Hellwig K, et al. Clin Immuno. 2013;149:219–24

-

Michel L, et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(8):796–802

-

Finer LB, et al. Conception. 2011;84(5):478–485

-

Fernández O, et al. Eur J Neurol.2018;25(5):739–46

-

MacDonald SC, et al. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(4):556–60

-

Montalban X, et al. Mult Scler. 2018;24(2):96–120

-

Dobson R, et al. Pract Neurol. 2019;19(2):106–14

-

Sandberg-Wollheim M, et al. Int J MS Care. 2018;20(1):9–14

-

Herbstritt S, et al. Mult Scler. 2016;22(6):810–16

-

Thiel S, et al. Mult Scler. 2016;22(6):801–9

-

WHO. Infant and young child nutrition. 2002. Available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/archive/pdf_files/wha55/ea5515.pdf (accessed May 2019)

-

Hellwig K, et al. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(10):1132–8

-

Langer-Gould A, et al. Neurology. 2017;89(6):1–7

-

Prévinaire JG, et al. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57(5):329–36

-

Pecori C, et al. BMC Neurology. 2014;14:114

-

Hellwig K, et al. J Neurol. 2010;257:580–3

-

Lu E, et al. CNS Drugs.2014;28(5):475–482

לאילו מצבים רפואיים קנביס רפואי יכול להועיל?

קראו עכשיו סיכום של מחקרים שבדקו את השפעת הקנאביס הרפואי על מצבים רפואיים שונים

לקריאה>>כתבות נוספות שאולי יעניינו אותך

רוצים להמשיך לקרוא?

הירשמו עכשיו בקלות ובמהירות לאתר התוכן של טבע ישראל לקהל הרפואי ותקבלו גישה לכל התכנים

להרשמהאת.ה עומד.ת לעזוב את העמוד

האם את.ה בטוח.ה?